Researchers at Stanford University have created a small device about the size of a quarter that will work with the energy from the sun to purify contaminated water in less than thirty minutes. The process, they claim, takes only two days and will destroy 99.99 of all the bacteria in the water it is tasked to purify.

Chong Liu, the lead author on the Stanford research, said that, “Our device looks like a little rectangle of black glass. We just drop it into the water and put everything under the sun and the sun did all the work.”

Direct sunlight can destroy bacteria in contaminated water but the process can take a while. With the new device, they can reduce the time to around twenty minutes. They believe, when it is ready for public consumption, that it will revolutionize many areas of the world, including the United States, so that drinking water will be safe to drink and to wash in.

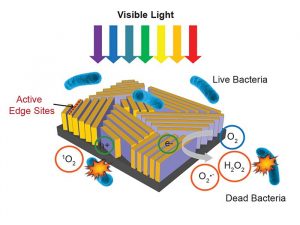

Almost all of the sun’s energy comes from what is known as the visible spectrum, the light we can see. Only about 4% of the sun’s energy comes from UV. The device is coated with a lubricant used in the manufacturing process called molybdenum disulfide. This chemical creates a multitude of other chemical reactions when it is in the water and being integrated with the sunlight. One of the chemicals generated in the flux is hydrogen peroxide which is a strong killer of bacteria and other germs.

“It’s very exciting,” continued Liu, “to see that by just designing a material you can achieve a good performance. It really works. Our intention is to solve environmental pollution problems so people can live better.”

This invention will be teamed with other recent inventions whose intent is to purify water or to pull clean water out of the air. The new device is cheap to produce and, unlike other processes, doesn’t need to have the water boiling before the process can begin and be effective.

The Stanford team looks to continue its research and experimentation. Thus far, they have treated the water for three particular types of bacteria. They want to test against more before they feel the device is ready for mass production and use.

PHOTO CREDIT: Stanford / Nature Nanotechnology